Published on 30 June 2023 in Indian Express

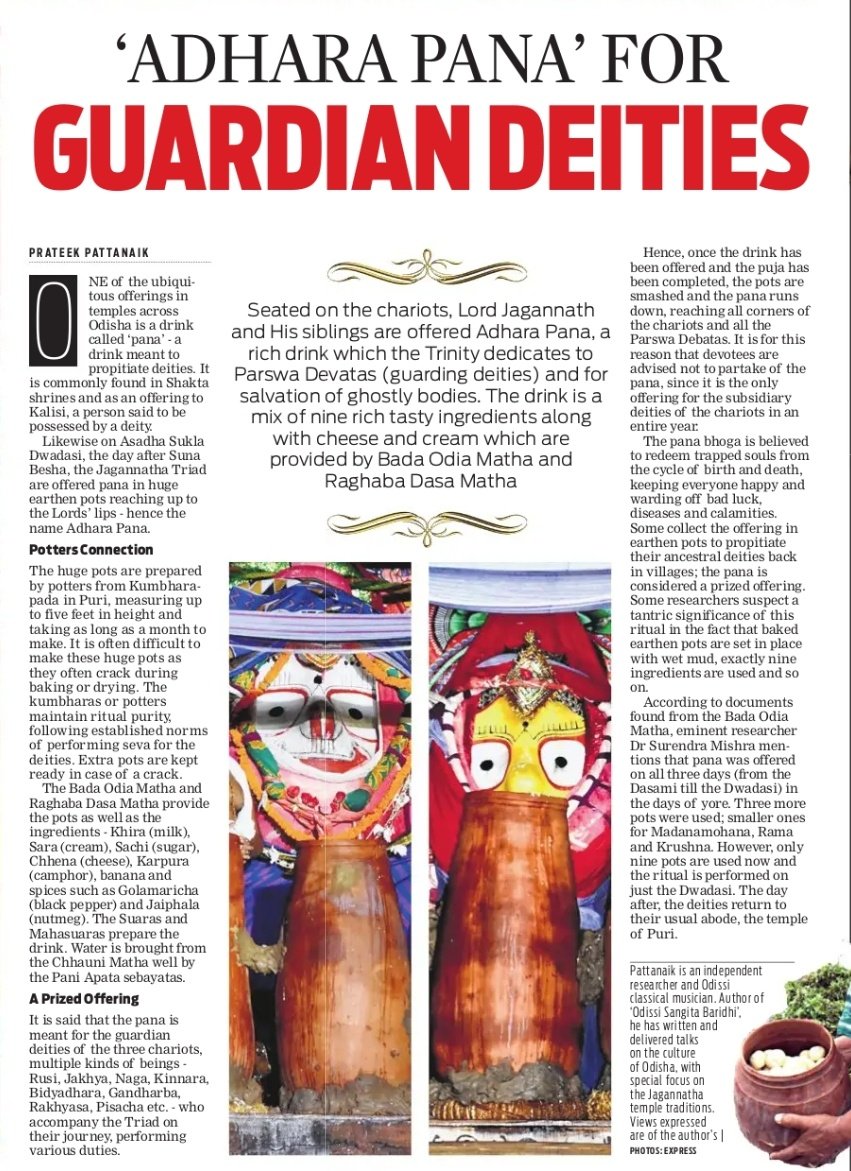

One of the ubiquitous offerings in temples across Odisha is a drink called Pana ; a cool drink meant to propitiate deities. It is commonly found in shakta shrines and as an offering to Kalisi, a person said to be possessed by a deity. Likewise, on Asadha Sukla Dwadasi, the day after Suna Besa, the Jagannatha triad are offered Pana in huge earthen pots reaching up to the Lords’ lips – hence the name Adhara Pana. The huge pots are prepared by potters from Kumbharapada, measuring up to five feet in height and taking as long as a month to make. It is often difficult to make these huge pots as they often crack during baking or drying. The kumbharas or potters maintain ritual purity, following established norms of performing seva for the deities. Extra pots are kept ready in case of a crack. The Bada Odia Matha and Raghaba Dasa Matha provide the pots as well as the ingredients – Khira (milk), Sara (cream), Sachi (sugar), Chhena (cheese), Karpura (camphor), banana and a spices such as Golamaricha (black pepper) and Jaiphala (nutmeg). The Suaras and Mahasuaras prepare the drink. Water is brought from the Chhauni Matha well by the Pani Apata sebayatas.

It is said that the Pana is meant for the guardian deities of the three Rathas, multiple kinds of beings : rusi, jakhya, naga, kinnara, bidyadhara, gandharba, rakhyasa, pisacha etc. who accompany the triad on their journey, performing various duties. Hence, once the drink has been offered and the puja has been completed, the pots are smashed and the Pana runs down, reaching all corners of the rathas and all the parswa debatas. It is for this reason that devotees are advised not to partake of the Pana, since it is the only offering for the subsidiary deities of the ratha in an entire year. The Pana bhoga is believed to redeem trapped souls from the cycle of birth and death, keeping everyone happt and warding off bad luck, diseases and calamities. Some collect the offering in earthen pots to propitiate their ancestral deities back in villages ; the Pana is considered a prized offering. Some researchers suspect a Tantric significance of this ritual in the fact that baked earthen pots are set in place with wet mud, exactly 9 ingredients are used and so on.

According to documents found from the Bada Odia Matha, eminent researcher Dr. Surendra Mishra mentions that Pana was offered on all three days (from the Dasami till the Dwadasi) in the days of yore. Three more pots were used ; smaller ones for Madanamohana, Rama and Krusna. However now, only nine pots are used and the ritual is performed on just the Dwadasi. The day after, the deities return to their usual abode, the temple of Puri.