Published on 2 Jul 2019 in OrissaPOST

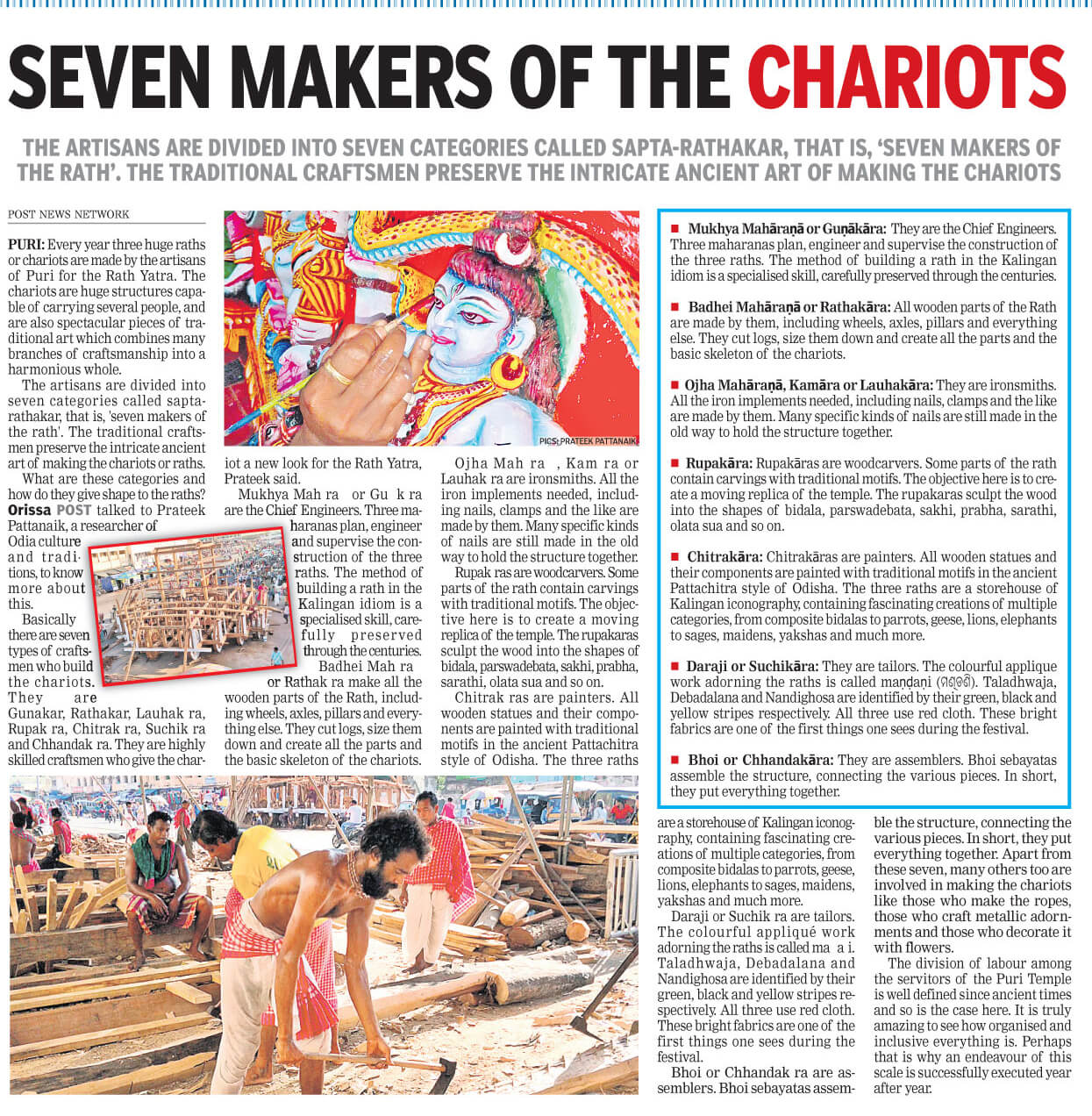

Every year for the Ratha Jatra, three huge rathas or chariots are made by artisans in Puri. While being huge structures that must be capable of supporting several people at once, the rathas are also spectacular pieces of traditional art, combining multiple branches of craftsmanship into a harmonious whole.

Traditionally the artisans are divided into seven categories called sapta-rathakāras, ‘seven makers of the ratha’. These traditional craftsmen hence preserve the intricate ancient art of making rathas. What are these categories and how do they work separately yet together to build the rathas?

1. Mukhya Mahāraṇā or Guṇākāra (ମୁଖ୍ୟ ମହାରଣା ବା ଗୁଣାକାର) : Chief engineers, so to say. Three maharanas plan, engineer and supervise the construction of the three rathas respectively. The method of building a ratha in the Kalingan idiom is a very specialised skill, carefully preserved for centuries.

2. Badhei Mahāraṇā or Rathakāra (ବଢ଼େଇ ମହାରଣା ବା ରଥକାର) : All the wooden parts of the Ratha are made by them, including the wheels, axles, pillars and everything else. They cut up logs, size them down and form all parts, creating the basic skeleton.

3. Ojha Mahāraṇā, Kamāra or Lauhakāra (ଓଝା ମହାରଣା, କମାର ବା ଲୌହକାର) : Ironsmiths. Iron implements needed, including nails, clamps and the like are all made by them. Several specific kinds of nails are still made in the old way to hold the structure together.

4. Rupakāra (ରୂପକାର) : Woodcarvers. Various parts of the ratha contain carvings of traditional motifs, the aim being to create a moving replica of the temple. The rupakaras sculpt the wood in the shape of bidala, parswadebata, sakhi, prabha, sarathi, olata sua and so on.

5. Chitrakāra (ଚିତ୍ରକାର) : Painters. All wooden statues and components are painted with traditional motifs in the ancient Pattachitra style of Odisha. The three rathas are a storehouse of Kalingan iconography, containing fascinating creatures of multiple categories, from composite bidalas to parrots, geese, lions, elephants to sages, maidens, yakshas and much more.

6. Daraji or Suchikāra (ଦରଜୀ ବା ସୂଚୀକାର) : Tailors. The colourful applique work adorning the rathas is known by the name maṇḍaṇi (ମଣ୍ଡଣି). Taladhwaja, Debadalana and Nandighosa are identified by their green, black and yellow stripes respectively. All three use the red cloth. These bright fabrics are one of the first things one sees during the festival.

7. Bhoi or Chhandakāra (ଭୋଇ ବା ଛନ୍ଦକାର) : Assemblers. The group of bhoi sebayatas assemble the structure, connecting pieces and putting it all together.

Besides these seven, many others are also engaged : including those who make the ropes, those who craft metallic adornments and those who decorate it with flowers. The division of labour among the servitors of the Puri temple is very well-defined since ancient times and so also is the case here. It is truly amazing to see how organised and inclusive the activity is— perhaps that is why an endeavour of this scale can be successfully accomplished, year after year.

The writer researches and documents vulnerable aspects of Odisha’s culture using technology. e-Mail: pattaprateek@gmail.com