Published on 9 Jul 2018 in OrissaPOST

Answered some questions on OrissaPOST.

Does the tradition of pulling a chariot exist elsewhere in Odisha?

Yes it does! Many different shrines across Odisha have their own chariot-pulling festivals. Most of these are emulations of the iconic Ratha Jatra of Jagannatha. Bhubaneswar’s famous Lingaraja Temple and Jajpur’s Biraja Temple both have their own Ratha Jatras, albeit at different times of the year. Lingaraja’s chariot is called Rukuna Ratha and Biraja’s is called Bijaya Ratha.

Even the magnificent Sun Temple of Konark might have had its own chariot festival. Mentioned in the ancient book of accounts of the Sun Temple is the construction of a 24 cubit high Ratha which was made by a group of 40 carpenters. Eight painters from Puri went to paint the chariots. This chariot festival was done on Magha Saptami, said to be Surya’s birthday. Even today, hundreds of people gather near the Chandrabhaga as per tradition.

What are some of the unusual traditions associated with Ratha Jatras across Odisha?

When the iconoclast Kalapahada attacked the Puri triad, the priests fled with the deities and concealed them in the deep pockets of Odisha. One such place was Marada in Ganjam, where the gods lived for almost two years. The temple was constructed atop a mountain and there was a huge canal surrounding the shrine hidden by dense forest cover. Due to this, conch shells were never blown or gongs beat for fear of drawing attention. To this day, the Marada temple has no Ratha Jatra. People still throng the empty singhasana with as much devotion though.

The Balarama Jiu Temple of Dhenkanal is presided by not Jagannatha, but his elder brother Balabhadra. And so it is the Ratha of Dhenkanal that moves first. Popular belief dictates that the younger brother waits for his elder to move first, and it is only after Dhenkanal that the Puri chariots can move.

We have innumerable such distinctions across the state. One can only list so much.

Everybody knows about Mausi Maa, Jagannatha’s aunt. Are there any other divine relatives?

Yes! In fact, Jagannatha is so deeply ingrained in Odisha’s cultural fabric that one finds a very complex net of beliefs across the state. And so, there is an entire divine family.

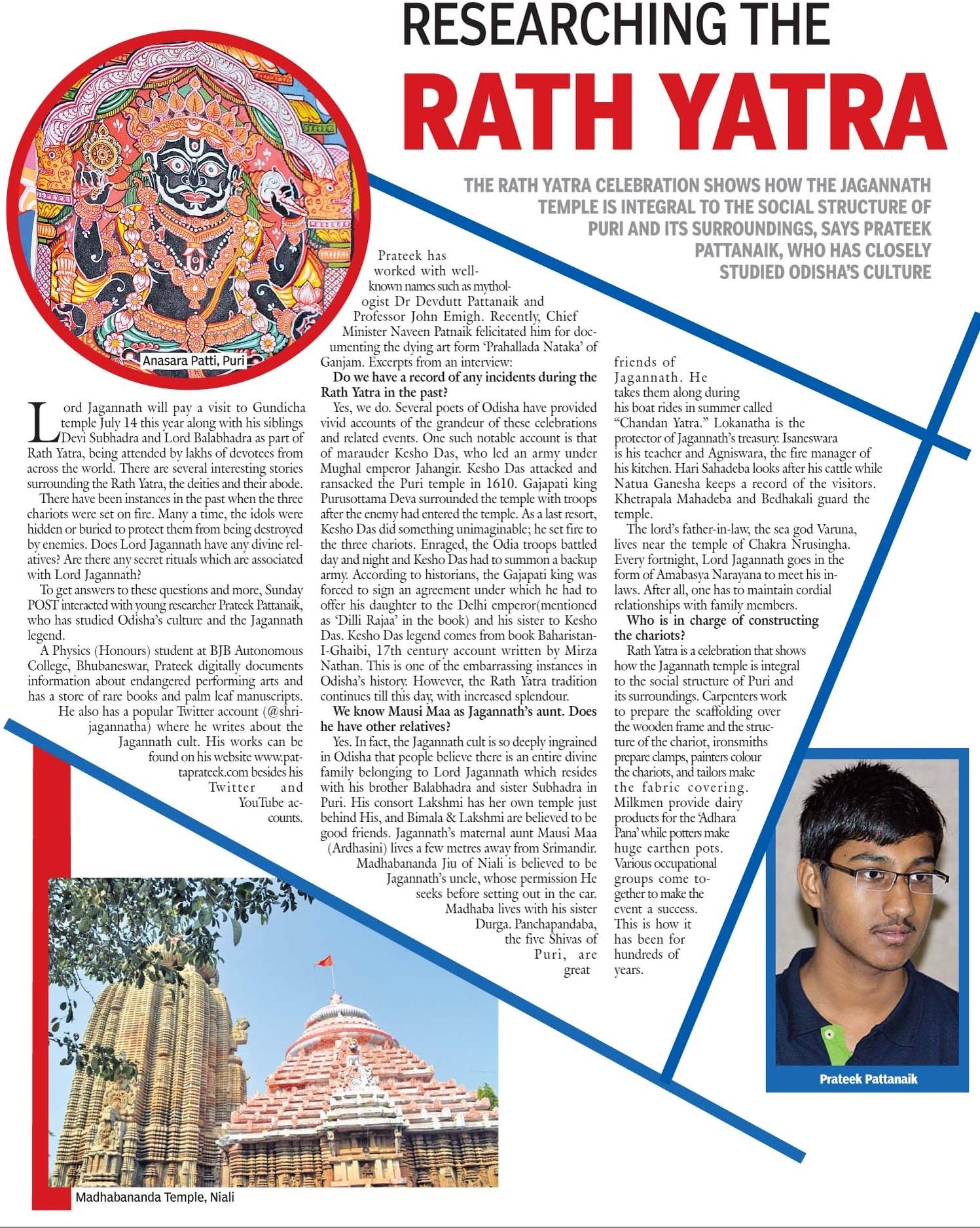

Jagannatha lives with his brother Balabhadra and sister Subhadra in the Puri Temple. Lakshmi has her own temple just behind his, and Bimala & Lakshmi are believed to be good friends. His maternal aunt Mausi Maa lives a few kilometres away but within the boundaries of Puri. Madhabananda Jiu of Niali is believed to be Jagannatha’s uncle, whose permission he seeks before starting out on his Ratha. Madhaba himself lives with his sister Durga. Panchupandaba, the five Shivas of Puri are good friends of Jagannatha; he takes them along during his summer boatrides. Lokanatha is the protector of Jagannatha’s treasury, Isaneswara his teacher and Agniswara the fire of his kitchen. Hari Sahadeba tends to his cattle while Natua Ganesa keeps a record of the visitors. Khetrapala Mahadeba and Bedhakali guard the temple.

His father-in-law, the sea-god Baruna lives near the temple of Chakra Nrusingha. Every fortnight, Jagannatha goes in the form of Amabasya Narayana to meet his in-laws. One has got to maintain good relations with family after all!

Which servitors work to give life to the Ratha Jatra?

Many classes of servitors. The Ratha Jatra forms a very good example of how the Jagannatha Temple binds the social structure of Puri and its surroundings. Carpenters work to make the wooden frame, woodcarvers carve the skeleton, ironsmiths prepare clamps, painters colour the chariots, tailors make the fabric covering. Milkmen provide dairy products for the Adhara Pana while potters make huge earthen pots. It is as if various occupational groups come together to make the event a success. Perhaps this is what has been driving this festival for hundreds of years.

Do we have accounts of the Ratha Jatras of the past?

Yes we do. Numerous poets of Odisha give vivid accounts of the grandeur of these celebrations. One of the notable accounts is the tale of the marauder Kesho Das, who led a big army under the Mughal emperor Jahangir. Around 1610, Kesho Das attacked and ransacked the Puri Temple. Gajapati Purusottama Deba, on getting this news immediately started out with an army and surrounded the temple, inside which were the enemy. In a last attempt, Kesho Das did something unimaginable; he set fire to the three Rathas. Enraged, the Odia troops battled day and night but Kesho Das had a last trick up his sleeve; he sent word and got a backup army. According to some historians, the Gajapati was forced to accede to an agreement under which he had to offer his daughter to the Delhi king and his sister to Kesho Das. This was one of the worst days in Odisha’s history. But even with so many attacks, Ratha Jatra still continues today, with increased splendour.

Why are certain rituals of the Jagannatha Temple secret?

Certain rituals like the Nabakalebara and Anasara are entirely out of public view. This is attributed to various reasons. The logical point of view is that the deities need to be painted afresh during Anasara and this isn’t possible in full view. The other side is that he is sick with fever and hence prefers isolation. We can only speculate; the secrecy surrounding these things is there for a reason.

A legend talks about Karnama Giri, a famous 12th-century tantric who was so proud of his occult powers that he decided to investigate the issue. He assured the king that this was a hoax and somehow managed to get him so that he could expose this great big lie that god could have a fever. He then turned into a bee and tried to fly inside but was overcome with a pungent scent and fled the place half-swooning. As a last attempt, he tried to turn invisible and follow a daitapati into the internal chamber. Karnama is said to have seen eight ladies sitting on an eight-petalled lotus. They chuckled at his stupidity. He could understand nothing and finally acknowledged his defeat. The dark Anasara chamber is still as mysterious.

Leave a Reply